The pandemic has raised a series of interesting questions about the adaptive and maladaptive aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Some have pointed out that there may be traits inherent to those with OCD that could be useful for keeping safe from COVID and reducing its spread. Attention to detail, tendency to track what objects have touched, and intolerance of uncertainty around contaminants may help some people adapt to a world of social distancing, mask use, and risk avoidance. However, while these qualities may have appeared to be assets in the early days of the pandemic, a basic understanding of how OCD works will make it clear that it adapts only to itself, not to reality. In other words, OCD exists in the realm of excessive certainty seeking, so external pressures to be more certain inevitably begin as a welcome adjustment and then evolve into the same nightmare as before. Enough is never enough for OCD.

In the spring, a series of videos and blogs circulated the internet telling us how to put our groceries away without touching them, how to handle the mail like it was poisonous, how to disinfect everything within eyesight, and more. People afraid of germs, bacteria, and viruses were equal parts terrified and comforted by new rules to follow. People concurrently afraid of chemicals suffered tremendously, stuck between the rock of not wanting COVID and the hard place of not wanting to come in contact with solvents they were sure would cause them and their loved ones cancer. While increased hand washing and disinfecting continue to be important safety measures (especially outside of the home), our understanding of the science of COVID transmission has evolved to emphasize social distancing, ventilation, and mask use. See here, here, and here.

A Compulsion Is Still a Compulsion

What often gets missed in the emphasis on staying clean from a “real” danger like COVID is that resisting compulsions still remains important. A compulsion is a certainty-seeking behavior that is out of proportion with a reasonable expectation of confidence. I am reasonably confident that washing my hands for 30 seconds with one pump of soap and warm water will get them clean enough to move on to my next task. Washing one’s hands for an hour in scalding water is a compulsion, regardless of whether its intention is to avoid the common cold or COVID. Ruminating for extended periods of time on whether you may have touched something contaminated is a compulsion, regardless of whether its intention is to be certain you are clean from the common cold or COVID.

Compulsions never make you safe. In fact, I would argue that compulsions always make you less safe if they persist. First, compulsive behaviors damage your probability compass. In other words, excessive certainty-seeking behaviors teach the brain that you are in a level of danger that is appropriate to the compulsion, not the reality. The longer an excessive ritual persists, the less confidence you can expect in your ability to gauge risk. The worse that gets, the more likely you are to be distracted by obsessive thoughts and end up failing to pay attention to potentially legitimate concerns. In my clinical work, I have seen countless OCD sufferers inadvertently take large and unnecessary risks, including accidentally harming themselves, in the process of trying to perfect their rituals and get certainty about their safety.

Second, there is no equilibrium in OCD. Compulsions are almost never contained. They often start out small, but then become more and more time consuming and complex. Remember, they function to compensate for an intolerance of uncertainty. But because certainty doesn’t exist, more and more effort is required to force the illusion of certainty each time. While the way we implement the gold standard of exposure and response prevention (ERP) may be slightly modified today, it remains the gold standard. For more on this, see “COVID-19 and OCD: Potential impact of exposure and response prevention therapy” by Sheu, McKay, and Storch (2020).

Circles of Flexibility

In the beginning of the pandemic, many of us went into total lockdown and separation from anyone not already living in our home. These days, due both to pandemic fatigue and a better understanding of COVID science, people are gradually opening up what I call ‘circles of flexibility.’ An example of this would be allowing your children to have a socially distanced playdate with a family you trust to be conscientious about COVID. Another might be choosing to go to the grocery store masked because you simply want the ingredients for something you feel like making, and not waiting to have it delivered or doing without.

Once in each of these circles, it’s important to know in what areas you may encounter a need for flexibility. For example, wearing a mask and staying six feet from other people at the grocery store is responsible. But there will be instances where you will be less than six feet from someone (e.g. passing by a customer in the aisle or handing your money to the cashier). In ERP terms, the exposure is deciding to open the circle of flexibility and the response prevention is accepting the inevitable inconsistencies within it. You will break the six foot rule at the store. Your kids will at some point touch each other in their otherwise socially distanced playdate. You will avoid, sanitize, or wash for one reason only to inexplicably choose not to avoid, sanitize or wash for a very similar one. Accepting this is the key to being able to enjoy your new experiences and keeping OCD outside the circle.

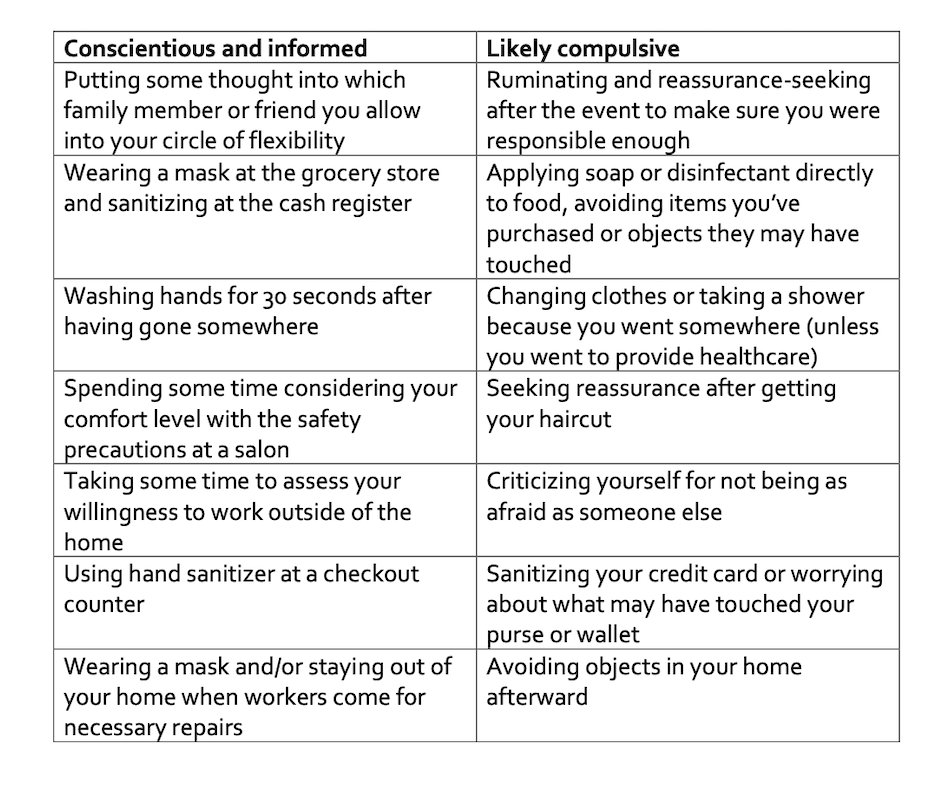

But how are we to tell the difference between reasonable safety measures and compulsive behaviors with a constant bombardment of conflicting information from the media, government officials, scientists, and even our therapists? Here’s a simple cheat sheet that may help:

No, this doesn’t cover everything, not even close. And yes, new information may come our way that changes the categories above. 2020 has not been sympathetic to those with OCD. All we can do is treat ourselves and others with compassion, and try to close the entry-points for OCD in the COVID age. The key to reduced suffering in the midst of this stage of the pandemic is to own your decisions. If you decide to enter a new circle of flexibility that you had once avoided, such as visiting a trusted relative you haven’t seen in months, it’s not enough to simply plan out your safety measures. You must also plan out your response to intrusive thoughts about whether you made the right decision.

We are social creatures and we need human contact sometimes. When we take the risk of entering a new circle of flexibility, we may be making an investment in our mental health. For this cost, we deserve to be present and to enjoy the people and activities we sought out, not squander them on rumination and self-doubt. For me, once I decided to start grocery shopping in person again, I made sure that self-care was more than just wearing a mask. I made sure it was also enjoying buying ingredients for new recipes and trying new foods. I want as much good as I can get out of this version of the world, and right now that means coming home with different kinds of pickled beets and weirdly shaped pastas I haven’t tried yet. For me, this is better than coming home with rumination and self-doubt.

-

Jon Hershfield, MFT

Director, The Center for OCD and AnxietySpecialties:Anxiety Disorders, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)